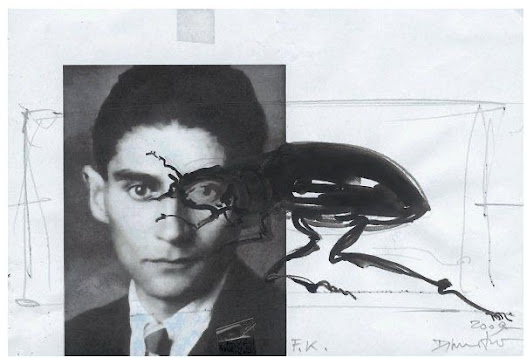

In the Face of the Insect: Kafka and the Impossible Existence

A philosophical reading of Franz Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis”

⸻

In a world that pretends to be balanced while rust consumes it from within, and on a gray morning without warning, “Gregor Samsa” wakes up to find himself transformed into a giant insect. This opening line in Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis is not mere absurd fantasy, but rather a rupture in the fabric of reality — a sudden crack in the wall of identity.

Kafka, caught between suffocating bureaucracy and haunted inner selves, does not write conventional narratives. Instead, he detonates a bitter existential question:

What if Gregor’s new form was not a transformation, but an unveiling?

Not of a man who became something vile, but of vileness that had always been there — hiding behind the mask of humanity.

⸻

Alienation as the Root of a Wasted Identity

Gregor Samsa was not loved — he was useful. A man reduced to a salary table, his worth measured by punctuality, not humanity. He supported his family, yet never saw them except through the bars of duty and necessity.

When the transformation occurred, the response was not emotional shock, but logistical crisis:

“What are we going to do with him?”

No one asked, “How does he feel?” — as if the self vanishes the moment it loses its function.

Here echoes Karl Marx and his concept of alienation when the worker is severed from the meaning of his labor. But Kafka moves beyond Marxism into a deeper realm:

An existential alienation — not just from labor, but from the body, language, the self, and the world.

As if man, per Heidegger, is a being thrown into existence without a map or language to understand himself.

⸻

The Body as a Space of Punishment

In his Discipline and Punish, Michel Foucault argues that the body is the first domain upon which power is exercised. It is shaped, monitored, and purified from deviance.

And in The Metamorphosis, the body becomes a theater for a silent punishment: not for a crime committed, but for the unveiling of what must not be seen.

Gregor was not deformed — he was stripped of his human shell. As if the world says:

“If you do not resemble us, we will show you as we fear you.”

And the horror lies in the fact that this unveiling is not a transformation, but a sudden truth:

When the masks fall, the ugliness that had always been there is revealed.

⸻

From “I” to “Condition”

Modernity, according to Max Weber, has disenchanted the world, reducing man to a number, a function, or a performance report.

When Gregor missed work, he wasn’t asked how he felt, but why he was late.

And when he failed to perform his role, he began to disappear. The sister recoiled, the mother panicked, the father attacked.

Thus emerges a harsh law governing social relationships:

“As long as you are useful, you are seen. If you falter, you are forgotten.”

In the words of Emil Cioran:

“What kills us is not death, but the world’s indifference to our cries.”

⸻

The Insect: An Unbearable Metaphor

Kafka deliberately avoids specifying the type of insect, leaving the door open for every interpretation.

This ambiguity is intentional: the insect is not a biological species, but a metaphor escaping definition.

It might symbolize rejection, illness, exile, or existential absurdity.

Each reader sees their own fear in it: loneliness, loss, futility.

And echoing Sartre’s “Hell is other people,” Kafka deepens the wound:

Hell is being seen for who you truly are… after you’ve lost the ability to pretend.

⸻

The Family: An Institution of Rejection, Not Shelter

If the family were a refuge, it would have embraced Gregor. But it was part of the same performance.

The father did not want a weak son, the mother collapsed in horror, and the sister grew weary of the burden of care.

They all loved him — not because he was him, but because he was productive.

Here, Kafka exposes the fragility of conditional love:

“As long as you are useful, you are loved. If you break down, love evaporates.”

The story even suggests that Gregor’s death was a relief to them all.

For the true metamorphosis was not in him alone… it was in them too.

⸻

Voice When It Turns into Form

When a person is long excluded from expression, their voice doesn’t disappear — it transforms into a shocking form.

Gregor didn’t protest, didn’t scream, didn’t object. He was silent, obedient, folded into himself.

But this silence finally exploded into a form that could not be ignored.

As Roland Barthes once said:

“Silence is the ultimate language.”

The transformation was not biological — it was a final language…

Finally, Gregor was heard — not through his voice, but through the distorted shape of his body.

⸻

The End: A Mirror That Reflects Nothing But Truth

Franz Kafka does not preach, nor does he offer solutions.

He merely places us in front of a cold mirror — then walks away.

He leaves us staring at Gregor, trying to deny the resemblance… but to no avail.

Because, deep down, we know:

• How many times have we been Gregor?

• How many times were we loved because we produced?

• How many times did we remain silent until the insect erupted within?

• And how many times did we become the metamorphosis… without anyone noticing?

Kafka does not answer.

Because he knows that the answers are not written… they are lived.

No comments:

Post a Comment